ENGLISH

ESSAY BY THE AUTHOR ALBERT RUSSO

.

FRANCAIS - Voir plus bas

THE WRITER AS A CHAMELEON, A BILINGUAL AND PLURICULTURAL ITINERARY ACROSS THREE CONTINENTS: by Albert Russo published in Taj Mahal Review

When you mention 'place', the words that initially come to mind are: 'home town', ‘roots', 'environment', 'culture’, the country you grew up in. The extended meaning of place, however, encompasses childhood, a 'territory' that is at once self-contained and very loose, because it is so unique to each one of us and so difficult to circumscribe, and to some, unfathomable. But place, to many of us, also conjures up the notion of exile, whether forced or not, and thus place becomes first and foremost language. For a number of reasons - one thinks of holocaust survivors or political refugees - some, after having acquired the language of their adoptive country, choose to relinquish their mother tongue, others, instead, cling to it with such fervor that it becomes a stumbling block. The choice of language in this case depends not only on economics or your acceptability on the part of the host nation, but upon a factor that is primariIy emotional, such as the attitude of your immediate family and what you wish, most of the time subconsciously, to conserve or to erase from the past.

A biIingual author - I write poetry, fiction and essays in both English and French, which I consider as my two mother tongues -, and a polyglot - I speak five languages with various degrees of fluency: the aforementioned, Italian, Spanish and German, in that order, with a smattering of Swahili and Dutch, and reading abilities in Portuguese -, l've had to confront a rare type of prejudice, mainly on the part of French editors and publishers, which is not the case, l'm glad to admit, in North America. Monolingual editors, however erudite they may be or appear - some, among them, can read in a foreign tongue often have difficulties in conceiving that one is capable of creating equally weIl in two languages. What makes the situation thornier is the relative scarcity of truly bilingual or even trilingual writers. Conrad, Nabokov and Beckett are the classical examples.

At a symposium held in Paris a few years ago on 'Writers and the Sea', Robert Cornevin, an eminent historian, literary critic and africanist, lamented over those French publishers who, through their stupidity and shortsightedness, had let Joseph Conrad exile himself into the English language, pointing out that the Polish writer had mastered French long before he could read Shakespeare in the original version. "We thus lost a monument of world literature to the British, he concluded, somewhat bitterly. In spite of arising nationalism, the situation, fortunately, is evolving and there is an increasing number of writers who no longer shy away from bilingualism. In the States, one can witness this transformation: there are more and more authors of hispanic background who choose to write in both Spanish and English. We're still talking, of course, of a tiny minority and for a long time to come, people who create in two languages will have to fight to impose their dual status. It is ironic that what ought to be considered an enrichment is too often looked down upon in the profession.

Where I’m concerned, it is only relatively recently that I have been accepted as a bilingual writer by the French critics, and consequently by publishers in Paris - I insist upon the 'consequently'. An eclectic writer, I escape any sort of labelling, which editors find very annoying, if not downright impertinent. So, many decide to ignore me altogether, the more adventurous pay some attention, whilst still keeping a comfortable distance. This lukewarm, noncomittal attitude may explain my propensity to take part in so many literary contests in the US, Britain and France, principally. Garnering prizes for me is an act of defiance, defiance against apriorisms. There is no fairer test than that of being judged anonymously. It is, l'm afraid to say, not at aIl the case with some of the national contests like the prestigious Prix Goncourt or the Prix Renaudot in France, which smack of pre-election scheming and reward, year in and year out - exceptions do occur once in a blue moon - the same three or four publishers, which I calI the sacred quartett, for the Prix Goncourt is more a publisher's prize than an author's. So much said for ethical practice.

Reverting to the notion of place and language, I have to smile when, having won an award, l'm referred to as an American writer or a French one, depending on the country in which the contest took place. Then there is the instance where the US editor, partially aware of my background, sends me a letter of rejection, with the pretext that my style is too European, whatever that means.

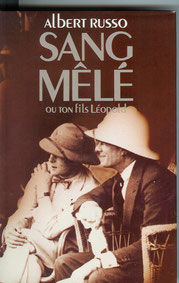

Born in the former Belgian Congo (contemporary Congo/Zaire) of a Rhodesian mother and an Italian father who came originally from the island of Rhodes, with sephardic roots that go back to the period of the Spanish Inquisition, I could never adhere to any notion of race, regardless of the color of my skin. Having spent my formative years mainly in Congo and Burundi, with frequent sojourns in Zimbabwe and South Africa, I consider the Black Continent not only to be my birthplace but the cradle of humanity. Africa has left an indelible mark on me and I deem it part of my heritage. Having known its beauty, the generosity of its peoples, and witnessed the turmoils of Independence in at least four countries, I cannot remain insensitive to its development, its tragedies and its hopes. The fact that apartheid is now history can only make me rejoice, which does not mean, of course, that the problems in South Africa will be resolved during this generation.

Here is an excerpt from my story THE EXAMINATION (it appeared in Short Story International) which evolved into a novel entitled LE CAP DES ILLUSIONS (DEVIL'S PEAK), published a few years ago by Editions du Griot in France.

“Jan, she insisted, "we can't keep Prudence on the farm any more. She'll be ten soon, and she hardly knows how to read. The child needs an education. Really, I don't want her getting entangled in this mediocre existence of ours. With a degree in her hands, she will be able to make her way in the city, and we will follow her ... Oh, how sick I am of this life!” Martha complained, bitterly. ...

That morning, aIl three of them were up before cock-crow. The little girl's seagray eyes sparkled; she was aIl prepared to go, squeezed into a short dress with puffy sleeves; a satin ribbon held up her frizzy hair; out of white socks rose a pair of bony, sunburnt legs. She stood leaning against the door of the pick-up truck, fidgeting with impatience. Yes! They were going to teach her to count and write properly. She was going to penetrate the mystery of books, and play with other children at blindman's buff. A beatific smile disclosed her teeth, which seemed to capture at a stroke the freshness of dawn. Jan tossed a checkered canvas valise on the luggage-rack.

"So, here we are on the road to high adventure” he said in a raucous tone, pinching his daughter's cheeks, more to convince himself than to reassure the child. Wedged in between her parents, Prudence embraced the undulating hills, as if for the first time.

Ablaze under a copper sun, the veldt gradually slipped away behind them in spirals of dust. ...

Classes began the following morning, in a relentless heat. Although gifted with a keen intelligence, the newcomer was admitted into first grade; as a result, she was taller and older than her classmates. When the bell rang for recess, Prudence rejoined the third graders, knowing that she'd feel more at ease in their company. She was soon approached by Greta and yolande who took to her immediately; they talked about the customs and the rules of the school, and about their friendships.

A scrawny redheaded boy unexpectedly accosted the three girls; his wavy hair was shot with bronze gleams, his pug nose looked as if it had been polished by a file.

"Hey, firstgrader! You’re pretty big for your class, if you ask me. What hole did you crawl out Of?” he jeered at Prudence in a nasal voice.

“Pay no attention to that little snot, Prudence; picking on girls is aIl he's good for," Greta interposed unceremoniously. The boy pretended not to hear. He went on addressing the new girl: "Lost your tongue, huh? Say, you’re kind of dark, though, aren’t you? Actually, you remind me of my maid. No, your hair isn’t as kinky as hers. AlI the same ...”

Outraged, Yolande blurted: “Just what are you getting at? l saw her mother and father yesterday; they're as lily-white as you. Oh, leave us alone!”

During class a phrase echoed in Prudence's mind like a hammer thumping against a wooden board: "I AM NOT COLORED, l AM NOT COLORED, l'M AN AFRIKANER! ...” Petrified, the child was undergoing a slow metamorphosis; she no longer understood the sole language she possessed, a language that had become aIl at once hateful to her ears. The thumping resumed in her head. She saw shadows closing around the assembly, then thought she heard claps of thunder: one, two, ten salvoes, succeeding one another as though vomited from an invisible machinegun.

"Show me your fingers, l won1t bite you," ordered one of the officers. "Look at her nails,” said his colleague, "there's no doubt about it, the blue halfmoons constitute irrefutable evidence. This kid’s got mixed blood!"

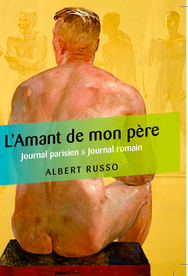

After Africa, my family moved to Milan, Italy, where l spent eight years, then l went to settle in New York City for about the same length of time, and here l am finally in Paris, France, where l've been residing for the past twenty-three years. In between, l have to mention the academic year spent in Heidelberg, Germany, and another one in Belgium, not counting trips to the People’s Republic of China, India, Sri Lanka, the Mediterranean and Continental Europe.

Place can be the atmosphere of a city or the figment of one’s imagination. At times, to escape reality, l write fantasy or science-fiction, with forays into surrealism and absurd humor, or a combination of the last two.

As an illustration, l'd like to read a story l've Ititled NEW YORK BONUS (published in Dreams and Visions, in Canada):

“Gladys felt radiant on this last summer evening, strolling through Central Park. It was her fifth day in Manhattan and she'd seen a lot of the city already, discovering its museums, going to Broadway shows, visiting Wall Street and the Village. She dared to take the subway a couple of times at noon, but mainly she traveled by bus and on foot. She marveled at the diversity the metropolis offered, at its stark contrasts, from posh Fifth Avenue to the seedy atmosphere of the Bowery. The only organized tour she took was to Harlem and the Cloisters. She'd heard and read a great deal about the dangers of New York City. In the lower East Side she did come across a few drunkards, cussing hobos and drug addicts, but accepted them as part of the city's folklore. Though she never ventured in the so-called hot spots after sunset, she was surprised to find how communicative and helpful New Yorkers could be. Even the squirrels in the Park seemed to beckon her with the greeting, "Welcome to the Big Apple, stranger!" Yet, amid the motley crowds, she very soon shed her 'foreign' look and meshed with the surroundings as if she'd lived there for years. Had she not won that lottery ticket at the Senior Citizens' charity dinner, Gladys would never have dreamt of leaving the perimeter of her Welsh village. And there she was, at seventy-five, awakening to a whole new gamut of emotions. "How splendidly resourceful is the human soul," she remarked to herself when a tall bulky fellow accompanied by a boxer swung the door open for her as she entered the lobby of her hotel.

The man, a middle-aged negro, clad in an expensive beige suit - double-breasted jacket, satin shirt and matching brogues - kept his dark glasses on and silently led Gladys into the elevator whilst the boxer blinked up at its master with expectant watery eyes. "Stop fretting, Lady!" the man commanded in a stentorian voice. Gladys' gaze instantly leapt towards the ceiling, searching for an escape, and finally settled on the floor directory. The words still vibrating against the metallic walls whithin which she felt trapped, Gladys stood petrified. As her breathing slackened, like that of a hibernating lizard, her mind began to brim with apocalyptic images and flash warnings that translated into newspaper captions: "Welsh septuagenarian assaulted by black mobster and his mongrel ... Foreign matron mugged in hotel elevator then raped and stabbed to death..”

At this point a second order was fired, more ominous than the first one: “Sit, Lady, l said SIT!” It appeared at once that a blizzard invaded Gladys' head, emptying it of aIl thoughts. Eyes glued to the floor directory which had just marked number 14, the old woman, slowly, very cautiously, slid into a crouching position. Her knuckles squeaked like a pair of absorbers that badly needed oiling. Reduced as she was to the state of an obedient robot, she ignored the lament of mortal flesh. ‘35’, read her lackluster eyes. A moment later, the now familiar voice boomed again, hoarse and ominous: “Lie down, Lady, it's an order!” It took only seconds before Gladys stretched herself on the elevator's thick carpeting. ‘39’, indicated the directory. Though she did not move, Gladys had the sudden and disagreeable impression that she was being immersed in a pool of sweat, or was it blood? She then perceived strange noises which grew closer and closer, like a veiled growl. She felt very wet and realized that someone or something was slobbering aIl over her face, more something than someone. Could it be ... a dog's tongue? The elevator beeped to a halt.

The next morning Gladys found herself in a quandary and kept asking herself, “Was that a nightmare, or did i t really happen? It seems impossible.”

As she crossed the lobby towards the reception area she noticed an envelope in her key slot. “Here, Ma'am,” the young employee said, “There’s a message for you” “A message?” she repeated, incredulous, “but I don’t know a soul in this town.”

This is what the note contained: “Dear Gladys, l hope you don't mind me calling you by your first name. Please accept my apologies for the inconvenience my boxer, Lady, and l caused you yesterday in the elevator. l must confess however that never in my life have l laughed so much. So that you may forgive us both, l'd like to extend you this invitation. You are personally requested to dine this evening at the ‘Top of the World’ where my jazz band performs. You cannot miss me, l am the saxophone player.

Cordially yours, L.J.J. (yes, the famous L.J.J.)”

To conclude, I shall refer to two of my stories - they are included in my collection, The Crowded World of Solitude, volume 1 (www.xlibris.com): VENITIAN THRESHOLD, with a strong sense of place, since the action oscillates between wartime Germany and contemporary Venice (this story has appeared in US, English, French, Belgian and Greek reviews and was selected by the Auschwitz Foundation}, and a tale of absurd humor entitled INTERACTIVE RIPOV, where place is aIl in the mind.

Responding to French publishers who want to put us, plurilingual and multicultural writers, in a box:

Do we all have to fit within a specific slot? Where does that leave freedom of thought and of expression? Aren’t the writer and the artist in any case considered outcasts of a sort? Take the case of a few famous authors. Nabokov started writing in Russian, then in French then in English. What was he, a Russian writer turned French, an AngloAmerican writer? And Joseph Conrad who was born Polish and who wrote also in French? He didn’t know a word of English before he was 20 and then too, spoke it with a terrble accent, but nowadays he is considered a British writer! Take Kafka who was Czech but who chose to write in German; his German was pedantic, i.e. not natural, since he did not live in a German-speaking country. I have Czech acquaintances who still consider him a ‘traitor’ for not having written in his ‘mother tongue’. Of course, I strongly disagree with that kind of reasoning. And the list continues with Beckett who wrote most of his plays in French but reverted to English occasionally. Etc...

So, I do have a more complex background than most living writers and I do belong to a tiny minority of a group that is already cast at the fringe of society.

FRANCAIS

ALBERT RUSSO ET LE BILINGUISME,

UNE EXPERIENCE D'ECRITURE

Essai d'Eric Tessier, paru dans la revue "Passerelles" N°26

Une étude fondée sur deux textes d´Albert Russo : “Ecrit dans le sang / Written in blood", extraits des romans “L’Ancêtre Noire /The Black Ancestor", et "Zapinette Vidéo / Zapinette Video - Oh Zaperetta!”

Albert Russo est bilingue. Il a grandi "en français et en

anglais." Mieux : chacune de ces langues s´est colorée des épices d´un parcours infiniment riche, qui le vit naître au Zaïre, belge de père italien et de mère anglaise, le fit grandir en Afrique,

puis traverser les océans pour gagner l´Amérique puis l´Europe (Italie et France).

Au-delà d´un intérêt évident pour le langage et d´une aisance

dans l´apprentissage des langues (il en parle six ou sept), cela a conduit Albert Russo à s´exprimer en tant qu´auteur dans ce que je nommerais ses deux "langues parentales."

NB : Notons au passage que la part francophone d´Albert Russo est elle-même issue d´une culture au moins bilingue puisque sont parlés en Belgique le Français et le Flamand (sans compter la minorité germanophone d´Eupen, aux confins des Ardennes).

Y a-t-il une langue prédominante ? La réponse a été claire : non. Français et Anglais font partie intégrante de lui. La notion de prééminence n´a aucun sens. Il suffit d´une opportunité, de l´état d´esprit du moment, de ce qu´il a envie de raconter, ou plus exactement de la façon dont il a envie de le raconter. Chacune des deux langues nourrit son oeuvre dans sa globalité, enrichies qu´elles sont, comme je l´ai signalé plus haut, par les différentes strates traversées:

- pour le français : français d´Afrique, français de Belgique, français de France - on pourrait également citer le français de Zapinette (pour les connaisseurs) qui est en passe de devenir une

langue à part entière.

- pour l´anglais : anglais britannique, américain, anglais rhodésien (très britannique), anglais sud-africain (c´est à dire mâtiné d´Afrikaans, la langue des colons d´origine hollandaise, les

Boers, elle-même composite puisque dérivée du Hollandais, dont elle est une version simplifiée, et intégrant nombre de mots Zoulous).

Les romans ou poésies d´Albert Russo sont publiés aussi bien dans le monde francophone que dans le monde anglophone. Comment résoudre alors la ô combien délicate question de la traduction? Et d´abord, y a-t-il traduction ?

Albert Russo rejette le terme pour employer celui d´adaptation. En effet, une langue ne se réduit évidemment pas à son vocabulaire, mais véhicule une culture, c´est à dire des références, des

mentalités, en bref tout ce qui construit une vision du monde particulière et commune aux différents groupes l´utilisant. Le travail d´Albert Russo consiste donc à raconter la même histoire en la

soumettant à la contrainte des différences culturelles,

contraintes qu´il maîtrise car elles sont en lui. Le texte n´est donc pas tout à fait le même en français et en anglais. Il n´y a pas traduction, mais autre version.

Ces diverses versions peuvent aussi bien être extrêmement proches l´une de l´autre, comme s´éloigner au point que la fin, menée par la logique d´une vision spécifique à une langue, peut varier du

tout au tout.

Une courte étude du texte "Ecrit dans le sang / Written in the

blood" va me permettre d´illustrer mon propos.

Résumons le passage choisi: Léodine est une adolescente, fruit de l´union d´une fille de colon belge et d´un GI américain, rencontré en France à la fin de la seconde guerre mondiale. Elle habite

en Afrique, au Katanga. Son oncle Jeff lui explique un jour que sa grand-mère paternelle était noire et qu´elle-même, par conséquent, l´est, même si cela ne se voit pas physiquement. Léodine est

profondément remuée par cette révélation et tente de se recomposer, de retrouver des repères dans la société coloniale où elle vit.

Léodine, découvrant en français qu´elle est une mulâtre : "Mon Dieu, je suis donc, je suis donc moi-même..." murmurai-je, comme si je venais de prendre conscience de cette vérité et qu´il fallait absolument que je la prononce afin de me convaincre que je n´avais pas mal entendu, "une métisse, une café-au-lait.""

La version anglaise est sensiblement

différente : "My God, this means that I too am..." I muttered, unable to complete the sentence, for the awesome truth had just pierced through my consciousness. It couldn´t be possible, there had

to be a mistake, I went on mutely, even trying to erase the word "mulatto" from my mind, as if it were a disease."

En fait, la réaction de Léodine est exactement l´inverse qu´en

Français. En effet, dans la version française, elle doit prononcer le mot pour se convaincre de la réalité de sa condition, tandis que dans la version anglaise, muette (mutely), incapable

de

poursuivre sa phrase (unable to complete the sentence), elle tente de le gommer (even trying to erase the word) pour n´avoir surtout pas à le prononcer !

Le choc est également exprimé de manière plus tendue, plus détaillée, en anglais - la vérité, par exemple, est impressionnante (awesome). Plus réactive aussi, puisque Léodine se débat franchement

contre elle : ça n´est pas possible, il doit y avoir une erreur (It couldn´t be possible, there had to be a mistake), avant de conclure sur : j´essayais d´effacer le mot de mon esprit, comme si

c´était une maladie (as if it were a disease).

Dans le même ordre d´idée, la description que Léodine fait d´elle est plus lyrique en anglais, et son apparence pas tout à fait la même.

- Version française : "Mes cheveux étaient toujours aussi soyeux et châtains, mes yeux, toujours couleur vert-noisette."

- Version anglaise : Les cheveux sont toujours châtains mais avec des éclats dorés (with gleams of gold), les yeux ne sont plus vert-noisette mais d´un beau bleu-vert (lovely blue-green hue)

évoquant la couleur du ciel ou celle des hauts-fonds d´un lagon à la clarté limpide - vierge de toute pollution (evoked the sky or the shoals of an unspoilt lagoon). De plus, en ce qui concerne

les cheveux, l´accent est mis sur un élément qui sort de la description pure et fait appel à l´affectif, puisque Léodine précise qu´ils plaisent à sa grand-mère qui aime enrouler leurs boucles

autour de son doigt (which so pleased my grandmother, who liked to twirl her finger around my locks).

Je n´irais pas plus loin dans une analyse de texte qui pourrait vite s´avérer fastidieuse. Il y a d´autres exemples qui parsèment le texte, mais ceux-ci me paraissent suffisamment parlants.

Mon idée n´est pas de démontrer qu´une version est plus riche, plus étoffée qu´une autre, mais que les rythmes dans l´écriture, les repères, sont différents selon la langue employée. En adaptant

plus qu´en traduisant, Albert Russo intègre son récit, sans

le trahir ni le dévoyer, dans un contexte bien précis : celui du public à qui il est destiné. Il s´agit de créer un équilibre entre fidélité au texte (quant au fond) et prise en compte du lecteur

dans sa culture.

Cet équilibre se trouve entre deux notions :

1) transposer la dynamique d´un texte d´une langue à une autre,

2) dépasser la forme pour mieux faire passer le fond, ce qui peut choquer les tenants de la sacralité du texte, car nous sommes là aux extrêmes de l´adaptation: recadrer, réévaluer, rééclairer,

quitte à transformer, sans écrire une autre histoire.

Une brève étude du roman Zapinette nous en dira plus.

Zapinette, dans la version française, est le surnom de Jeannette Villiers, fillette de douze ans vivant à Paris entre sa mère (célibataire) et son oncle.

Dans la version anglaise, Zapinette s´appelle Esmeralda

McInnerny et est à moitié américaine. Il s´ensuit une série de différences entre les deux Zapinette, Esmeralda s´avérant par exemple, moins naïve que Jeannette, ou plus exactement moins

enfantine. Dans sa vision du monde, et dans son vocabulaire même. En effet, l´une des particularités de Zapinette est de triturer le langage, de le décortiquer pour en extraire l´humour et la

poésie qui colorent notre quotidien et que nous ne savons que trop rarement percevoir. Ainsi "époustouflant" devient "et-pousse-ton-flan", "grandiloquant" "grand-du-loquant", "nonagénaire"

"gagagénère", "à qui mieux mieux" "à qui meuh meuh".

Chez Jeannette, c´est la spontanéité qui s´exprime, et la distorsion semble ressortir de l´inconscient, qui s´appuierait sur la maladresse de manipulation du langage caractéristique des jeunes

enfants. Chez Esmeralda, par contre, on sent une intentionnalité, une maîtrise plus grande du mot, comme si elle avait grandi plus vite (trop vite ?) que Jeannette. L´une est plus nature, l´autre

plus mature. Pourtant, quel que soit la manière dont se manifeste ce jeu sur la langue, le résultat est le même :

un regard critique, ironique sur le monde et ses occupants.

Evidemment, la possibilité d´adapter est le privilège de l´auteur, et il paraît inconcevable qu´un traducteur prenne autant de liberté avec un texte qui n´est pas sien - nonobstant quelques

exemples célèbres qui virent, entre autres, Baudelaire s´emparer des "Confessions" de Thomas de Quincey, et Antonin Artaud du "Moine" de Gregory Lewis.

Ce court essai livre cependant cette expérience qu´est le bilinguisme chez Albert Russo à la réflexion du lecteur. L´exemple d´Albert Russo me paraît primordial, dans le sens où il utilise au mieux cet outil formidable pour réussir ce pari (quelque part) insensé et délicat qu´est, pour une oeuvre, le passage d´une langue à une autre.

Eric Tessier

Les textes d´Albert Russo :

- "Ecrit dans le sang" (Les Cahiers du Sens - France 2002)

- "Written in blood" (Spinnings Magazine - USA 2002)

- "Zapinette Vidéo" (éditions Hors Commerce - France 1996)

- "Zapinette Video - Oh Zaperetta!” (Xlibris Corporation - USA 1998).

Eric Tessier, Rédacteur-en-chef de la Nef des Fous

THE ROSE CITY OF PETRA

by Albert Russo

Won an Honorable Mention in the 78th Annual

Writer’s Digest Writing Competition

Behind the mount of Hor

where Aaron is buried

in the Valley of Moses

the Nabateans built palaces of splendor

carved in the rock

lofty canyons scraping the sky of a limpid

translucent blue

Surrounded by the desert

a thousand walls sprout in phantasmal hues

from sand pink to coal brown

through all the shades of coral

defying the laws of gravity

Walking in the narrow corridors that separate them

you feel at once dwarfed and exhilirated

imagining you are the emissary of a foreign court

awaited by the King of Petra

And the towering walls stand guard, protecting you

all the way to the palace

Then all of a sudden as if emerging from a dream

between the cracks of a gorge

a doric column appears

holding parts of a monumental crown

An ethereal silence sets in and you slow your pace

lest the miracle fades into a mirage

the air is brimming with sand particles

yet you fear that if you remain still

you will be turned into a pillar of salt

like Lot’s wife in the Bible

your feet shuffle on the pebbly ground

and the crunching sound fills you with terror

then in a surge of courage you slip out of the crack

and face the majestic facade of the golden Khaznah

THE STAGES OF LOVE

by Albert Russo

Won an Honorable Mention in the 4th Annual Writer’s Digest Poetry Awards

diaphanous blue

cloven by the Eiffel Tower

in your virgin space

a veil of dust

draping my body

the sound of your breath

velo di polvere

vestendo il mio corpo

il tuo respiro

iridescent dot

sucked into a chalice

flower tongues ladybug

the moment your lips meet

you can kiss friendship goodbye

the flesh takes over

bocca a bocca

non è più amicizia

la carne vince

skin against skin

and the magic operates

till the cells rebel

the difference between

a sex maniac and a lover

body temperature

la differenza tra

maniaco ed amante

temperatura

beware dear lovers

passion is a clash of wills

bound to implode

he fell in love with her,

but she looked elsewhere, smitten,

his heart a gaping wound

s’innamoro di lei

senza rendersi conto

solitudine

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

They call me Gianni

They call me Jim

But also Dominic

In both genders

In every guise

Whether it be Gianni, Jim or Dominic

In the present tense as in the past

First or third person

We're talking of the same person

With the difference that each one

Speaks in another tongue

Confounding strangers

Claims the spiteful gossip

At times Gianni and Jim will be one and the same

At times they will oppose each other

Sometimes they might act as total strangers

And so it goes for both Dominics

The distance between them may be paper thin

Or else wide as the ocean

That which separates two languages

Or lies, mute, within the blood cells

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Mon nom est Gianni

Mon nom est Jim

Mais aussi Dominique

Dans les deux sens

Et donc dans tous les sens

Que se soit Gianni, Jim ou Dominique

Au present comme au passé

A la première personne ou à la troisième

Il s'agit de la même personne

A ceci près que chacune d'entre elles

Est marquée par le sceau d'une langue

L'assaut, diront les esprits chagrins

Tantôt Gianni et Jim se confondront

Tantôt ils s'opposeront

Tantôt ils ne se reconnaîtront plus

Et il en sera de même avec les deux Dominique

Parfois l’écart entre eux sera infime

Ou alors aussi vaste qu'un océan

Celui qui sépare les idiomes

Ou se mesure à la mixité du Sang

DISSOLVING THE MASQUERADE

for some mysterious reason,

in the middle of the pedestrian square,

they felt their clothes loosen and fray

like dandelions caught by a storm

and, averting each other's eyes

as that mute and invisible alien

stripped them to the skin,

they suddenly stopped running about

in the middle of the square

never had there been such a sight

hands twirling like mad dervishes

hands that spun more swiftly

than the windmills of Friesland

hands which played legerdemain

for an unpaying and bedazzled audience

in the middle of the square

the people had all but vanished

leaving in their stead

the only possession they had

which could claim true authenticity

THEIR OWN BARE HANDS

in the middle of the square

there were long diaphanous hands

hands thick and veined as chipolatas

gnarled hands that cried for solace

craftman's hands mottled with splinters

hands whose fingers knew the printed word

so intimately, the whorls could be read in italics

and whilst all hands are pure and innocent

some of them, lovingly manicured

belonged to high class thieves

others, downy as a foal's nape

glinted with particles of cocaine dust

the birds that nested under the awnings of the square

feasted their eyes upon this choreography in Hands Major

twittering to their hearts' delight

as surely they must have eons ago

long, long before their biped cousins

had invented the art of masquerade

in the middle of the square

through the whims of gods

for a fraction of eternity

man had only nature to clothe his soul

L'ART DE LA MASCARADE

pour on ne sait quelle mystérieuse raison

au beau milieu de la piazza

ils sentirent leurs vêtements s'effilocher

autour de leurs membres

s'éparpillant aux quatre vents

comme des pétales de fleurs déssechées

s'éludant du regard, tandis que l'invisible

étranger les soumettait à ce bizarre et collectif effeuillage

ils cessèrent soudain de s'agiter

dans cette piazza, jamais auparavant

ne s'était produit pareil spectacle

les mains se mirent à tournoyer comme de fols derviches

des mains qui fouettaient I'air avec une rage d'éolienne

mains de prestidigitateurs évoluant

devant une assemblée impromptue de badauds médusés

la piazza semblait à présent soudain désertée

ils s'étaient tous évanouis, laissant à leur place

le seul bien qui ne pouvait les trahir

une foule dense de mains nues

au milieu de la piazza

se profilaient de longues mains diaphanes

des mains rougeaudes et veinées à l'aspect de chipolatas

des mains ratatinées hurlant leur solitude

ou d'autres encore dont les doigts connaissaient

les caractères d'imprimerie si intimement

que l'on pouvait lire en italique chacune de leurs volutes

et tandis que toute main est innocente et pure

certaines, lisses comme de la porcelaine

appartenaient à des voleurs à la tire

d'autres encore, duveteuses comme la nuque d'un chamois,

étaient pailletées de poudre de cocaine

depuis les auvents et les marquises

qui surplombaient la piazza

les moineaux et quelques colombes

se rengorgeaient à la vue de cette chorégraphie

puis, comme par enchantement,

le concert muet en ut majeur à mille mains

fut accompagné de roucoulades et de gazouillis

comme l'on devait en entendre bien avant

que l'homme n'eût inventé l'art de la mascarade

THE ROUNDNESS OF YOU

I want to say it in a thousand tongues

yet none said it better than my own

and since you are no longer in the flesh

it is everywhere that I want you to be,

like now, at Franco’s deli

where I have just bought some Parmesan cheese

grainy and slightly moist, piangente

the way you always insisted,

it melts in my mouth

and I savor the roundness of you

tondo, tondo, liscio come una luna d’avorio

I needed you to go for a while

then you misunderstood me and left, you thought, forever

but you didn’t count with that roundness of you

with which my whole being was besotted

how you would laugh when I sang the marvels of your skin

dans tes rondeurs encore je me glisse

this evening I asked the confectioner's

for your favorite marzipan chocolate

and I ate it on my way home,

then again that whiff

and the ineffable roundness of you

gold auf weiss, rund herum wie deine feurigen Augen

half asleep, my lips drunk with your milk

whilst a hand cupped your buttocks

as if God had no other designs for it

la redondez de tus pies

oh I couldn't resist that pair of blue suede shoes

and had the pretty blonde attendant try them,

remember, the one with whom you shared the same size?

she sold them to me for a song

I could go on and on

exhausting Babel

and its myriad tongues to evoke the roundness of you,

which indeed I shall do, for that taste of eternity

LE GALBE DE TON CORPS

je voudrais te le dire dans toutes les lanques du monde

mais aucune ne le peut mieux que la mienne

et puisque tu n'es plus là

c'est partout que je veux que tu sois

comme à présent, chez l’épicier italien

qui m'emballe ce morceau de parmesan

au grain juste ce qu'il faut de moëlleux

piangente , comme tu l'aimes

en le laissant fondre dans ma bouche

c'est le goût de ton aîne qui me revient

tondo, tondo, liscio come una luna d'avorio

je voulais que tu t'en ailles quelque temps

tu m'as mal compris et m’as quitté pour toujours

seulement, vois-tu, tu avais oublié

que de ta peau j'étais affolé

et comme tu riais lorsque je chantais

les merveilles de tes courbes

and forever I shall savor the roundness of you

ce soir j'ai demandé au pâtissier

le biscuit de massepain nappé au chocolat dont tu raffoles

en rentrant j'en ai fait une bouchée

ce goût ineffable du galbe de tes seins

gold auf weiss, rund herum wie deine feurigen Augen

entre somme et veille, mes lèvres empreintes de ta liqueur

tandis que ma main couvre ton sexe

comme si Dieu ne lui avait trouvé d'autre dessein

las curvas suaves de tus pies

n'ayant pu résister devant ces chaussons de daim bleu

j'ai prié la vendeuse de les essayer

tu t'en souviens, celle qui a la même pointure que toi

elle me les a refilés pour une bouchée de pain

je pourrais continuer ainsi à l'infini

remontant jusques à la cime de Babel

évoquer dans toutes les langues le galbe de ton corps

ce que je ferai assurément pour te rendre immortelle