REVIEWS & CONTRIBUTIONS

CRITIQUES & REVUES LITTERAIRES

Around the world / Autour du monde…

North America: Confrontation, Amelia, Cicada,The Linden Lane Review, Potpourri, Pearl Muse, The Voyeur, Kindred Spirit, Art/Life magazine, New Thought Journal, Negative Capability, O’zone, St. Cuthbert’s Treasury Annual, Manna, Poetry Northwest, Ally, The Third Eye, The Literary Review, Unveiling, Confluent Education Journal, Verve, Pandora, Frank,The Ecphorizer (a Mensa review), Eureka Literary Magazine, Seedcloud, A Writer’s Choice Literary Journal, Academic & Arts Press, Snow Summits in the Sun Anthology (The Cerulean Press), The Plowman, Légèreté Press, Skyline magazine, Phoenix, River King Poetry Supplement, The Poet, Zephyr, Unveiling, Philadelphia Poets, Quest Publications, Asylum, Postscriptum, Waves, Iliad Press, World News, A Different Drummer, Termino, The Poetry Conspiracy, The New England Anthology of Poetry ; The Review of Contemporary Fiction, Archaeology Impulse (Copyright University of Toronto, 2005), Books In Canada, Oasis magazine (Arizona, 2008).

Great Britain: Ambit, The Edinburgh Review, Passport, Interactions, Orbis, Lines Review, Chapman, Peninsular, Helicon, Reach, New Hope International, Passport, Psychopoetica, World Wide Writers, The European Journal of Psychology, Prospice, Envoi, Poetry Now, Presence, Time Haiku, The Haiku Quarterly, The Acorn Haiku Anthology, Still, Retort, Buzzwords, Sepia magazine, The Yeats Club, Prospice, Stirred not shaken.

India: Poet, Quest, Chandrabhaga, Replica magazine, Wanderlust, Parnassus of World Poetry, International Poetry, The Still Horizon anthology, The Millenium Peace annual anthologies, The Taj Mahal Review / Cyberwit.net/

Sri Lanka: : The Island.

Japan: Printer Matter.

Australia: Dreams & Visions.

Africa: Okike (Chinua Achebe’s Review), Prize Africa (Zimbabwe), Papier blanc Encre noire (Kinshasa / Brussels), http://www.boloji.com/memoirs/104.htm - essay by Dr Amitabh Mitra (South Africa) on Albert Russo's African novels.

Continental Europe:

The International Herald Tribune (Paris), Cosmopolitan (Dutch edition), Playboy magazine (French edition), La Nef des Fous, Place aux Sens, L’Autre Journal, Labor, Libération, Poètes et Romanciers à la Bibliothèque Naguib Mahfouz, Les Cahiers du Sens, Odra (Poland), The Auschwitz Foundation Bulletin, Sivullinen, Stranger than Madness, Fremde Verse, Los Muestros, Plurilingual Europe.

Albert Russo’s Poetry prizes and accolades include:

in the US: An honorable mention in the 2000 Robert Penn Warren poetry contest and Editors’ choice in 2004, several Amelia (California), Pearl Muse and New York Poetry Forum awards, Marguerette Cummins Broadside Award, Editors’ choice award at the National Library of Poetry, Southern California Poetry contest award, etc. His His large collection encompassing 30 years of poetry, The Crowded World of Solitude: Volume 2, was a Runner-up in the 2008 BEACH BOOK FESTIVAL sponsored JM Northern Media of Hollywood, CA - Their properties include The DIY Convention: Do It Yourself in Film, Music & Books; The DIY Music Festival; The DIY Film Festival; The DIY Book Festival; The New York Book Festival; The Hollywood Book Festival; OFFtheCHARTS.com; The DIYReporter.com; BookFestivals.com; and this site.

in the UK: The Yeats Club Poetry Award of Merit, several Reach awards and honorable mentions, 2 Best Overseas Poetry awards from the annual AAS (Eileen & Albert Sanders) poetry competitions, Interactions Poetry Award (Jersey), 2003 Forward Press 100 Poets (selected from over 50,000 entries), etc.

in India: the 2002 Millenium Michael Madhusudan Academy Award for Poetry (including a five-day invitation at their Calcutta venue), several poetry awards and honorable mentions from The Poet and Parnassus World Poetry, etc.

*Winner of the 2008 AZsacra International Poetry Award sponsored by the Taj Mahal Review, India - prize: 500 US$ - http://cyberwit.net/

in Norway : He’s been invited as a featured poet at the International Literature Festival held in Oslo during three days in September 2008.

in Malaysia : He’s been invited as a featured poet at the Kuala Lumpur World Poetry Reading held in the country’s capital from the 3rd to the 8th November 2008.

He’s been a member of the jury of the Prix Européen for over 25 years (sitting on the panel with Ionesco until his death) and sat in 1996 on the panel of the prestigious Neustadt Prize for Literature, which often leads to the Nobel Prize.

Visit his literary websites, describing his 55-odd books of fiction and poetry in his two mother-tongues, English and French, which include 25 photobooks

www.albertrusso.eu + www.authorsden.com/albertrusso

Comments on a variety of Albert Russo’s work:

JAMES BALDWIN: on Mixed Blood and other works. “l've read everything you sent me and l like your writing very much indeed. It has a very gentle surface and a savage undertow. You are saying something which no one particularly wants to hear and saying it, furthermore from a particularly intimidating point of view. You're a dangerous man.”

JOSEPH KESSEL (Académie Française): “... l was very touched by the tone of your two books.”

PIERRE EMMANUEL (Académie Française):. “... l want to tell you the pleasure l had upon reading those difficult, sensuous pages ... yet full of humor.”

DOUGLAS PARMEE (Queens'College, Cambridge, GB): “... l was particularly impressed by the remarkable range shown in such a small space, and the extraordinary command of the language.”

MICHEL DROIT (Académie Française): “ ... Much imagination, sensitivity and quality of style ... one really feels your Africa.”

PAUL WILLEMS (Curator of the Brussels Museum of Fine Arts and Author): “From the onset l felt a new tone to which one cannot remain indifferent.”

About "Eclats de malachite" ("Splinters of malachite") :

GEORGES SION, in Le Soir:”The author is endowed with rich experiences, a vast knowledge of languages and strong emotions which influence his style ...”

Jeune Afrique: “... Largely autobiographical, this work is written in the manner of an exorcism, it is engrossing and reveals a very real talent.” Vie et Succès: “Nostalgia of childhood depicted by a great writer.”

Mwanga (Zaire) : "”.. a work of universal appeal ... the human message is the 'fetish' which vibrates in the author's book.”

About "La pointe du Diable" ("Devil’s Peak"):

ROBERT CORNEVIN in Culture française: “the author's sensitivity matches the quality of the descriptions.”

Vie Ouvrière, Paris: “...His prose is that of a poet wounded by the claws of a ferocious society.”

Tribune juive: “In a very personal style, Russo denounces the shame of apartheid. He speaks as a poet when describing the beauty of Africa.”

Concerning his apartheid novel "Le Cap des illusions", Ed. du Griot, Paris:

- Mensuel littéraire et poétique, Brussels: "...his discreet lyrical style in this novel has the quality of certain classics, yet at times, the author is closer to poets like Dos Passos or Aimé Césaire. From this eminent polyglot such forays are not surprising. But above all, this is South Africa depicted by someone who knows it intimately well. And Albert Russo succeeds in giving us a lesson in ethnology with a verve few masters could possibly match."

- La Cité, Brussels: "... Prudence is raised as a poor white Afrikaner, but one day, the apartheid witch sneaks into her new school under the guise of a freckled classmate, then, brutally, the little girl will be wrenched from her roots and thrust amid the Colored community of District Six, compelled to share henceforth the fate of the underdog. Here, the absurdity of apartheid is scanned by a writer whose style is the reflection of his soul, in which language and culture constantly crossfertilize. And, ultimately, he leads us to believe in a Cape of hope.

about "Futureyes / Dans la nuit bleu-fauve", his bilingual poetry anthology,

Ed. Le Nouvel Athanor, Paris:

- The French Review, USA: "...this esthetically superb bilingual volume reveals the poet's shadowy and wild inner climate in carefully incized subtle gradations. Within these inner confines, Russo invites us to penetrate his densely imaged cosmic verse. Russo is an unforgettable poet who, time and time again, compels the reader to that ever fertile, elusive, and mysterious land of the creative artist."

This review was signed by Bettina Knapp who has authored more than 45 books

on literary criticism.

- Mensuel littéaire at poétique, Brussels: "... this whole volume is an 'Emergency call' (title of one of the poems) to lost brother / & sisterhood.

ENGLISH

.

AUTHOR SPOTLIGHT - Albert Russo

Whether it's setting the story in Senegal and Kenya, speaking of a wise child’s deceptively worldly innocence, or recreating through a young African boy’s joys and struggles of the tensions of modern life, author Albert Russo interlaces his stories around life’s general issues.

Albert speaks seven languages and loves to interact with people of different cultures and horizons. He has lived in three different continents, which opened his mind to the world's variety of cultures and ways of thinking. Albert abhors any type of violence and especially those incited by the so-called 'men of god' whose sole preoccupation is power, revenge and murder, in other words terrorism, which is the plague of our century.

Albert Russo is well-known for his excellent books. He released his first book in 1998 called Zapinette Video through Xlibris. We invite you to look at his more than 20 trade and picture books, including 'The benevolent American in the heart of darkness', 'The crowded world of solitude', volumes 1 (stories) and 2 (poetry), as well as his photo books, 'Mexicana', 'Sri Lanka' and 'Italia Nostra', among others.

He is a recipient of many awards, such as the American Society of Writers Fiction Award, The British Diversity Short Story Award, several New York Poetry Forum Awards, Amelia Prose and Poetry Awards and the Prix Colette, among others.

“I have many inspirations, from people like Moses, Jesus, Buddha, Einstein, Nelson Mandela, Mahatma Gandhi and Muhammad Yunus who helps thousands of poor people set up their own small businesses. People who build, give hope and love to their fellow humans, as opposed to those who just want to destroy innocent lives thinking they will become martyrs,” Albert says.

General introduction to Albert Russo’s work by Martin Tucker:

Albert Russo’s art and life are all of a unique piece, and that piece is a plurality of cultures. Born in what was then the Belgian Congo and now is Congo/Zaire, he grew up in Central and Southern Africa and writes in both English and French, his two ‘mother tongues’. With his intense interest in African life, the young Russo also engaged with knowledge beyond narrow stratifications of colonial custom. As a youth he left Africa for college in New York (where he attended New York University). For many years he has been resident in Paris.

Wherever he has lived, Russo has concerned himself with one hard-burning commitment: to achieve an illumination of vision in his writing that suggests by the force of its light some direction for understanding of human behavior and action. He draws on the many cultures he has been privileged to know, and he is always respectul of diversity. But Russo is no mere reporter. While he works with words, and while his work is concerned with place and the spirit of place, he is more interested in visitation than visits. Almost every fiction Russo has written involves a visitation, a hearing from another world that reverberates into a dénouement and revolution of the protagonist’s present condition. These visitations are of course a form of fabulism--that is, utilizing the fable as a subtext of the animal nature of man. Russo’s fabulism however is not in the line of traditional mythology (perhaps mythologies is a better term, since Russo draws from a variety of folklore and consummate literary executions). In one of his recent fictions, for example, he writes of a man who falls in love with a tree--his love is so ardent he wills himself into a tree in order to root out any foreignness in his love affair. Thus, Russo’s “family tree”, the mating of woodland Adam and Eve, becomes in his creation not only a multicultural act but a cross-fertilization of the cultures he has drawn from. In this personal fable Russo suggests the Greek myth of Pan love and even the Adamastor legend, that Titan who has turned cruelly into a rock out of unbridled passion for a goddess. Russo suggests other legends as well, and certainly the crossing of boundaries, psychological, emotional as well as physical and territorial--hybrid phenomena now sweeping into the attention of all of Africa and the Middle East--is to be found within the feelingful contours of his tale. Fabulism is now a recognized presence in our literary lives. It goes by other names: magic realism is one of them. Underneath all the manifestations of this phenomenon is the artistic credo that creation is larger than life, and that the progeny created enhances the life that gave being to it. In sum, the artist is saying that life is larger than life if given the opportunity to be lived magnificently. Russo’s is certainly a part of this willingness to experiment beyond the observable. His fiction represents, in essence, a belief, in the endless perceivable possibilities of mind. Its humor is at times dark, however, and perhaps this color of mood is a reflection of Russo’s background and biography. For his art, while enlarging, is not showered with sun. His dark hues are those of ironic vision. Russo may be said to be very much a part of the end of this century. His concentration is on the inevitabilities of unknowingness; thus his resort is to the superrational as a way of steadying himself in the darkness. At the same time his work cannot be said to be tragic, for the unending endings of his fictions suggest a chance of progress, if not completion of one’s appointed task, worlds meet and become larger worlds in Russo’s work; people change within his hands. It is a pleasure to pay homage to Russo’s achievement.

Critic and professor of English at C. W. Post of Long Island University, MARTIN TUCKER has published over twenty volumes of literary criticism, among them The Critical Temper, Modern Commonwealth Literature, and Modern British Literature (in Continuum's Library of Literary Criticism series). He is the editor of the prize-winning literary journal Confrontation, and the author of Africa in Modern Literature and other works. His poetry has been collected in Homes ot Locks and mysteries (1982), and appears in leading periodicals. He is a member of the Executive Board of PEN American Center and has served on the Governing Board of Poetry Society of America. He has also written a biography of Joseph Conrad and of Sam Shepard, both critically acclaimed. He has also recently contributed to the Encyclopedia of American Literature (A Literary Guild Selection).

"ALBERT RUSSO: Poet as photographer / Photographer as poet".

Essay by Adam Donaldson Powell

published in the December 2007 issue of Taj Mahal Review, India

Of some fifty-five book publications to-date, eighteen of Russo’s books are photographic essays. These titles include impressions from travels around the world, quirkiness and humour in human experience, studies of sculptures, autobiographical essays with photography as the medium, and more. Had Russo not had such a passion for art and literature, he would surely have had a fine career as a photojournalist for commercial publishers of travel books, travel guides and travel magazines. However, Russo’s inclination towards the artistic and social elements of human predicament and expression, coupled with his love of poetry, has resulted in a myriad of publications which effectively express poetic and literary curiosity through poetry’s modern-day “first cousin”: photography. I use the word “curiosity” intentionally as Russo never forces his impressions upon us as an expression of “truth”, but rather guides us through his own personal experiences and thoughts through visual exposés. Sometimes the progressive order of photographs in some of his books can seem somewhat illogical as Russo presents us with his own “connections” between impressions as he sees them as an artist – rather than grouping photographs in an order that an advertising executive or commercial travel book might choose. This is Russo’s prerogative, his perspective .. and an important aspect of his own unique poetic expression.

Some of his photography books are combinations of texts and pictures, and others are without texts. The absence of titles is a bold artistic statement in itself, relying upon the strength and the progression of photographs themselves to tell the author’s/photographer’s personal story. Personally, I prefer the books that consist of photographs alone as I do not always relate to the accompanying texts and find them sometimes to be as annoying as I find signatures on the front side of paintings (when the signatures not only do not add to the overall work of art, but actually detract from the viewing experience). But this is a question of personal taste. Having a background both within visual art and poetry, I – like Albert Russo – am capable of understanding the “poetry” in the photographic presentations without explanation or added literary decoration. I think this is true for many (if not most) persons who enjoy photography books as works of art.

Russo’s photographic essays to-date include: “A poetic biography”, “Brussels ride”, “Chinese puzzle”, “City of lovers”, “Granada”, “En / in France”, “Israel at heart”, “Italia nostra”, “Mexicana”, “New York at heart”, “Pasión de España”, “Quirk”, “Rainbow nature”, “Saint-Malo”, “Sardinia”, “Sri Lanka”, and his newest: “Body glorious” and “Norway to Spitzberg” (both released in 2007). These are almost exclusively full-colour photos .. a medium which Russo plays with combining childlike naiveté and curiosity for the unusual aspects of the “banal”, and exciting excursions into the nature and the planet’s overall cultural diversity, with a broad palette of professional techniques. Russo goes to great pains to mix traditional images with their contemporary partners and counterparts, and to play with exposure, light, filters and clarity/non-clarity in order to exaggerate aspects of the culture and to communicate his own personal experiences and sensations. I would like to see a photographic essay by Albert Russo, in which he translates his interactive communication between photographer/poet and subject to the medium of black and white photography. I am certain that Russo would find even more exciting nuances and enigmatic photographic puzzles through the usage of light, shadows, layers of greyness etc., which would even further enhance his natural highly-effective ability to penetrate beyond picture-taking .. and far, far into the inner energy forms and thoughts of his photographic subjects/objects and their surrounding environment/conditions.

Perhaps the most unusual photographic essay is his “A Poetic Biography”, published in 2006. The book is exactly what the title suggests: a collection of photographs of Russo, his family members and friends in various situations and environments, and over a period of several decades. Here Russo includes both photographs of people (colour and some black and white), photographs of letters and telefaxes, telegrams, articles on Russo as an author etc. – all without explanation or commentary. In this way, Russo uses the classic “first person” style of prose-writing to create an almost surrealistic glimpse into the inner reaches of Russo’s personality, history, personal life, ambitions and self-identity. The book leaves us with a yearning to discover that personal aspect which Russo has not commented on, but which most other artists and authors usually make no bones about proclaiming ad nauseam: namely, his dreams .. and what his life might have been like otherwise.

Another fun and beautiful photographic exposé is Russo’s latest book: “Norway to Spitzberg”. I have previously reviewed this book and commented:

“Albert Russo's photographic essay illustrating a cruise ship voyage with the Costa Atlantica («La città ideale») along the coast of Norway, from the city of Bergen (birthplace of composer Edvard Grieg) to the top of the globe (Spitzberg) is fascinating not only because of his realizing the full circle of «post-post-realism» in modern photography, but also because Mr. Russo transforms the tourist «photo-stalker» experience into the creation of a professional visual compendium – combining dramatic and magnificent seascapes, fjordscapes and landscapes with the intimacy of still lifes, the humanity of people at work and play and in their quiet, alone moments, as well as the extremities of fauna, and indigenous peoples and their cultural expressions and living environments. It is not difficult to understand that Mr. Russo is also an accomplished poet and a master of prose-writing. The stories he tells in this photographic essay are not a mere show of proficiency as regards each individual work of art, but rather a dance of images as vivid as an operatic performance – full of passion, drama, silences, humour and music. Mr. Russo has employed a Canon digital Ixus 55 - 5.0 megapixels camera, with 3x optical zoom. His «eye» for discerning, and his talent for capturing the «photographic moment», the mastery of light and clarity vs. slight distortion etc. is a testament to his delicious sense of artistry as well as his empathy for the experience of being human.”

Out of curiosity, I took contact with Albert Russo to ask him to comment on his love for photography. Here is his comment:

“In response to your question: I've always liked photography, from my adolescent years in Africa, actually I loved filming too and my 8mm or super 8mm films looked more like stills than films, people would complain telling me, oh god, five minutes on the same object, flower, trees, landscape, whatever, enough already! Ever since my African days I've been taking photos with all kinds of cameras, from the standard Kodak box, to the famous German Minox, to the Fujica ST-605 (wonderful camera that accompanied me everywhere) - often using the Rexastar lens for close-ups (1:3.5 - f- 135mm), alternately with the smaller but very friendly Minolta 70W Riva zoom, and now with the Canon digital Ixus 55. I have probably forgotten a few other cameras I had. Oh I used to take many colour slides in Africa (which I still have tucked somewhere and should think of printing the best). Poetry and photography? They are always closely related. A good picture tells a thousand things to the beholder if he/she pays attention to it, and the 'right' word suggests a thousand other things, that is why I never like to simply write captions under my photos. Actually now I do not wish to write anything at all, the photo must speak to you on its own.”

In conclusion, I would recommend that art photography and poetry enthusiasts take note of this talented artist. As one who has reviewed his collected poetry and read many of his novels, short stories and essays, I can attest that his literary talent complements his photographic expression. Albert Russo is artistically self-integrated in all of his creative disciplines.

Copyright 2007, Adam Donaldson Powell.

Excerpted from Adam Donaldson Powell’s unconventional biography of Albert Russo

UNDER THE SHIRTTAILS OF ALBERT RUSSO, published by l’Aleph, Sweden

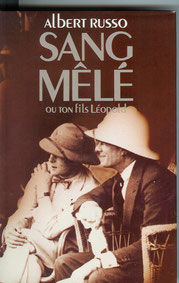

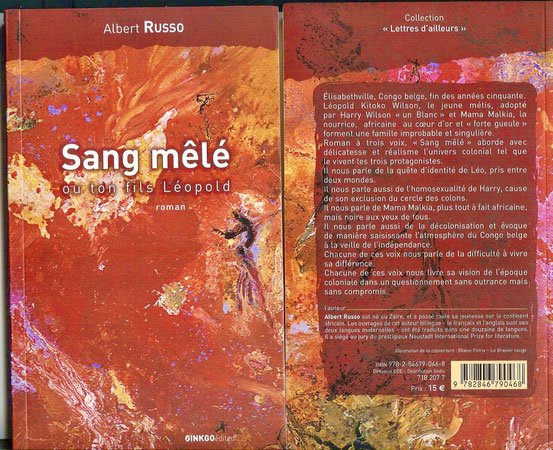

“The African Quatuor”, which includes “Adopted by an American Homosexual in the Belgian Congo” (formerly “Mixed Blood”), “Leodine of the Belgian Congo”, “Eur-African Exiles”, and “Eclipse over Lake Tanganyika”, was published in English by l’Aleph (Sweden) - both as e-books and as separate paperbacks - in 2014. Each of these four novels deals with the three African countries under Belgian rule, and during the post-colonial period: the present DRC (Congo Kinshasa / Zaire), Rwanda and Burundi. “Eur-African Exiles” also deals with Rhodesia / Zimbabwe and South Africa, during and after apartheid. All of these individual novels had been previously published by Domhan Books (USA), and then by Imago Press (USA). The French versions of these novels initially appeared in France as individual books: “Sang Mêlé”, “Eclipse sur le Lac Tanganyika”, “L’Ancêtre Noire” (later re-published with the title “Léodine L’Africaine”), and “Exils Africains”.

Albert Russo is a multilingual author, writing his original works and literary adaptations in English, French and Italian. It should be noted that while he started writing poetry, stories and essays in English (while studying Business Administration at New York University in 1963) in North America, the United Kingdom and other continents, his first published books were in French.

A popular adage in creative writing is: “Write what you know about”. Without opening up a hornet’s nest regarding this and other so-called “cardinal rules of writing”, it is likely most obvious to readers of Albert Russo’s novels based in Africa that he knows his subject, does massive research and also possesses tremendous ingenuity in elaborating and embellishing factual incidences into glorious literary expositions - which are both captivating, entertaining and informative. This talent cannot be easily taught in creative writing classes or at universities. It requires an active fantasy as well as the ability to fill in the blanks in stories from the news and personal life history, as well as to create a painterly background with details of the environment, history, politics, flora, fauna, foods, sounds, smells and much more. Albert Russo’s novels - especially the ones based on events in Africa - are rich in such descriptive imagery, and they provide every bit of visual and sensorial entertainment as a film or series of photographs.

Albert Russo’s first creative expression form was - in fact - photography, and he has taken photographs since he was a young lad. He received his first camera (a Kodak box camera) in 1955, and has published over 55 art photography books with exposés from his travels to exotic places all over the world. Among the awards received for photography books are: Indie Excellence Awards, The Gallery Photografica Award (Silver medal), and the London Book Festival Awards. In addition, his photos have been exhibited at the Museum of Photography (Lausanne, Switzerland), in the Musée du Louvre, at the Espace Cardin, both in Paris, at Times Square (New York City), whilst his two photography books on Paris and New York have been lauded by Michael Bloomberg (previous Mayor of New York City).

However, the greatest inspiration and tool for Albert Russo’s writing was and is his own uncanny ability to constantly co-interact both visually and conceptually with his surroundings, all the while linking fact and fiction inside his mind, and archiving this rich mélange of imagery together with his own experiences of mundane conversations and events suddenly brought to life - until the intensity of it all bubbles and brims over to a literary volcanic eruption which gives birth to both a sense of overall completion as well as inciting in the reader a desire to read, smell, see and hear ever more. In short, Albert Russo is a master of story-telling, armed with a poet’s tongue and the eyes of a photographer.

But how does Africa fit into his life and literature? Albert Russo’s life story is as exciting as his novels. He was born in Kamina, province of Katanga (Belgian Congo) in 1943, to an Italian Sephardic father (from Rhodes) and a British mother (who had grown up in Rhodesia). He and his family resided in Congo, Ruanda-Urundi and Rhodesia for seventeen years, during which time Albert also traveled often to South Africa. He graduated from high school in Bujumbura, Burundi (Athénée Royal Interracial) on the northeastern shore of Lake Tanganyika. By then he was already multilingual: speaking French, English, Dutch and German (and vernacular Swahili). His many years residing and traveling on the African continent provided Russo with much more than mere local stories to tell. His own family background and social position in a colonialized Africa slowly moving towards independence and coupled with his own thirst and hunger to discover and experience “the soul of Africa” has given way to a plethora of perspectives of historical and literary value, which might otherwise have been lost in the axis of time and change. Albert Russo IS African. Albert Russo IS of “mixed blood”, because blood does not only run in arteries and veins but in the social, cultural and creative DNA as well.

Let us take a closer look at “Mixed Blood” (“Sang Mêlé”) and the influences and events in Albert Russo’s life which created this fantastic story that has been published and re-published many times by various publishing houses on two continents.

I first read “Mixed Blood” (“Adopted by an American Homosexual in the Belgian Congo”) several years ago. Now, upon re-reading the work I am struck by the notion that the book is actually about identity. The shock of the titled themes “mixed blood” and “adoption by an American homosexual” - no less in the Belgian Congo - in contemporary Western first-world society now seems lessened by social change and human progress. Yes, while we have not come as far as many might wish, we have certainly come quite a way since post-WW2 and the year in which this novel was first published in France (1990). Of course, all literature and art must be seen at least partially in the contexts of the social and political contexts of its era. In that regard, the book was certainly rather shocking. But what about the more universal concepts and ideas that transcend epochs? The book does indeed deliver in a larger time frame as well - through the pervading and underlying universal theme of search for identity in a great sea of currents and elements (natural and not) which lead us, hinder us, and ultimately contribute to our self-definition and the ways in which we shape our lives … sometimes by way of our choices, and at other times in response to survival (eg. physically, mentally, socially and spiritually). We are all essentially co-creators of our states of mind and being, and always on the lookout for guidance, agreement and support for our ideas and choices. That guidance can come from various sources: religion, laws and regulations imposed by authorities, the media, families, friends and other social groups and institutions … and authors and artists. The latter can oftentimes see themselves as on the front lines in the war of minds. Sometimes as teachers and propagandists, but more often taking on the burden of encouraging and provoking the public to use their minds in expanded ways, to continue developing, and to become more accepting of one’s own need to live and think more creatively and with fewer restrictions and personal boundaries. This vital and sometimes “dangerous” role as a provocateur requires courage and the willingness to confront one’s own perceived limitations. This because in order to inspire introspection in others an author/artist must identify with humanity in ways that are believable and convincing. This is one of Albert Russo’s greatest strengths as an author. In all of his books he creates a mysterious mélange of personality confluences and interconnections, stories within stories, voices becoming other voices, and historical references that retain their relevances across decades and centuries.

In “Mixed Blood” there is an abrupt change of “first-person dialoguers”, eg. from Léo the son, and then halfway through the book to his father as he reads and reacts to a letter from Léo. At first reading, this literary mechanism might seem to be a simplified way of showing generational voices. In fact, I suspect that there was much more going on in the mind of Albert Russo when he penned this work. It is logical that by using the first-person the author is perhaps freer to become Léopold — more directly and more freely — while accessing his own experiences from life. Russo has a child’s genius when it comes to being inquisitive and at the same time omniscient, often noticing and dwelling upon small quirks that adults try to ignore but which children (rightly so) find quite significant, eg. the twitching of a person’s Adams’ apple. By writing as Léo in the first-person (just as he writes as Zapinette in several books in a later series) he is thus free to re-access these memories and fascinations that most of us dismiss and forget as we get older.

Russo’s employment of stories within stories (eg. Mama Malkia’s folktale, which adds an important psychological layer to an otherwise mundane relationship between herself, Harry and Léo), and his juxtapositions of other less significant stories within the main story, all serve to give the book great depth and a wider net range in which to capture and maintain readers’ interest. At times these well-written sub-plots function as short stories in their own right.

And then there are many underlying sub-themes which are mentioned briefly but in contexts which make them larger than life and utterly spell-binding, such as when a cut diamond is turned slightly to capture life from a different angle. These include, among others, American fascination with a perhaps glorified vision of Africa, Africans’ identification and sympathies with American Blacks not feeling free, homosexuality/pederasty, Blacks vs. Arabs, Blacks’ sympathy for Jews, African local culture vs. Christian institutions and morality, witch medicine vs. European medicine etc.

I have asked Mr. Russo to write me regarding many of these thoughts and questions, and also to explain the appeal of this book then, and now. This is his rather candid response:

I finished writing MIXED BLOOD, my first major African novel, in the Summer of 1986, and sent it immediately to James Baldwin, whom I met soon thereafter, for he had liked it very much. While in Paris we had dinner together and I accompanied him to a private showing of the film ‘Lady sings the Blues’ (Billie Holiday), of which, he had already penned a scathing review in America. He then kindly invited me to St. Paul de Vence in southern France, but unfortunately he died at the end if 1987, and it was too late. My second stay in the USA after Stonewall (not while I was studying there during Kennedy’s presidency) has probably influenced me to tackle the subject of homosexuality, which I had never done before.

I wrote the novel first in English and had won the Best Fiction Award by Volcano Review in California for the whole first part. Then I showed the English novel to Robert Cornevin, the president of ADELF (association of French-speaking writers) who told me that I absolutely had to translate it into French, so I rewrote and adapted it almost verbatim - you do know that I NEVER translate my books from English into French and vice-versa, I rewrite them, changing all the typical expressions of language A, as well as certain ‘images’, which I deem untranslatable. Professional translators are not allowed to do what I do. In certain cases, as in ‘I-sraeli Syndrome’, the English text is much more erotic than the French one, so yes, in some cases, there are additions. I feel freer to express myself in English than in French. ‘Ambiance oblige’. When the first French edition came out it was both a critical and a commercial success - all is relative -, but that is the book with which my literary career was launched in the French-speaking world.

The Black-American struggle had a definite impact on my writing. Not only because I have lived in the United States for a total duration of 8 years, two decades apart, but because I was born and grew up in an African colony, where there was racial discrimination. I had read quite a few white and African-American writers and was well aware of the history of racism in North America. Yet, if I had to publish the same novel for the 4th or 5th time today, I wouldn’t change a word, because I deem that my story is still valid today, maybe not contemporary in Scandinavia or in Holland, but definitely in France - and here, I don’t even mention the countries where you get jailed or, worse, decapitated if you are openly homosexual -: even though marriage between partners of the same sex is allowed, there are still millions of people demonstrating every year against that law and against same-sex couples having children. Homophobia hasn’t disappeared, and especially not in the French provinces. There are many more gay youths committing suicide than heterosexual teenagers. And something I never heard proffered out loud in the Belgian Congo (yes some of the people were hypocritical all right, but they never dared express those insults publicly) such as Sales Pédés,“on te fera la peau", which so many young Muslims shout in the streets when they happen to see two men holding hands. The irony of it all is that in Muslim countries homosexuality seems to be the norm (but you must never mention it). I know, I have been to the Maghreb countries and to Turkey many times. It seems paradoxical, but in my novel, i.e., in the Belgian Congo, gay people were not menaced as they are today. Of course, they were much more discreet too. That may also be the reason.

I often use the first person vs the third person in my novels in order to better identify with the protagonist and with the other main characters: I am that character and feel freer to delve into his or her anima.

Since the very beginning of my ‘career’ I have liked to include foreign words and expressions. Actually, I’m an African gifted with a number of languages, each language, being a planet in its own right. Africans have a natural gift for languages. Not only do they speak their own dialect, but they also speak one of the continent’s main languages like Swahili, plus the colonialist’s lingua franca: English, French, Spanish, Portuguese … Example: in Burundi, they speak Kirundi, Swahili and French; and those who go to university add English as well into their curriculum. This gift for languages was totally ignored during the colonial period! In France I’ve often been told that I have no roots. My answer: You are wrong. Compare me to that tropical aquatic plant whose roots develop out of the water (yes, indeed, upside down - ask a botanist and s/he will give you the latin name for this plant / tree). In America that wasn’t a problem. Only the French are Cartesian to the point of being intolerant.

Please note, dear readers, that from now on I shall use my own neologism ’s/he’ instead of ‘he or she’.

These are the themes that contributed to the success of this book: homosexuality, racial and cultural differences, plus the colonial and post-colonial era. I must insist on this: I went to Senegal (West Africa) about seven years ago and found the very same atmosphere, with the exception that the country was independent and that they had computers and mobile phones. But in the countryside, I felt exactly the way I felt when I was a teenager in the Belgian Congo and in Rwanda-Urundi. With the major difference that now we were on an equal footing. But all the other problems remained the same.

I’d like to point out the fact that I am not, nor have I ever been a gay militant. I’m just an author like many of my better peers, since I write all kinds of stories, stories which have nothing to do with gay themes. My family read all my novels and they knew very well who I was, my mother, sisters, children and now grand-children. They accept me with no questions asked, as well as my partner of 25 years, Bernard, whom they all like very much.

I never liked labels, and that is because of French intolerance: to them I am not an African, since I am not Black. The fact that I write in several languages, disturbs them and they - the big publishers - prefer to ignore me. What is this Albert Russo, they ask, who’s lived in Africa, then in America, then in Italy and who speaks French like a Frenchman? He is ‘nothing’, has no roots. In other words, in their eyes I’m a bastard - in the sense that I am too ‘mixed’ ; they might add, ‘too mixed-up’.

“Mixed Blood” has always been very well received in Africa/the Congo, and this hasn’t changed. Actually all my African books are being studied at the University of Lubumbashi (formerly Elisabethville) and probably in the other major Congolese, Rwandan and Burundian universities, both in the History and the Literature departments. That makes me very proud. My English versions are also read in Ghana, Nigeria, where Chinua Achebe published some excerpts in his own magazine, and in South Africa, where Zulu Zapinette was also published, not long ago.

I have been asked if I intended this story to be a novel. No, I never plan anything. I started writing and this book became a novel.

Robert Cornevin, of whom I spoke earlier read the original English manuscript and he enthusiastically prompted me to write a French version, which then became a success. Don’t ask me how or why it was first published as a book in French. Publishers worldwide - and here I include the ‘big’ American and British publishers - are irrational, they can even be commercially wrong, but they will never admit it. A bon entendeur salut!

I’ve also been asked how long it took me to write this novel. I’m a slow writer: I need a whole year for a book of 180 to 250 pages.

When I started writing “Mixed Blood” there was no Internet. I did a lot of research, the old way. I have read maybe 100+ books on African History, mores, tribal life, oral and written literature, pre-colonial, colonial and post colonial periods. I have read well-written and balanced books, as well as very badly-researched books, especially by Anglo-Saxon so-called renowned experts, who are terribly biased, even today, especially where Belgian rule in Africa is concerned. They insist on the personal and often ruthless rule of Léopold II, who used foreign, British, French and Belgian mercenaries, but also Stanley, the Welsh-American explorer-reporter, who drew the map of what is today the RD Congo, and whom many contemporary Africans are thankful for, in spite of some of his cruel deeds. After the ‘international scandal’ the British launched, Léopold II cast aside his ‘private’ property like a hot rod to the Belgian Parliament, which never wanted a colony in the first place. The British, and consequently the Americans actually put a cross on the most important period, going from 1908 to 1960 - that is when that huge territory, the size of Western Europe, 80 times larger than the new ‘mother country’, became the Belgian Congo, and when the Belgians began to ‘repair’ some of the worst aspects inherited by a king they never liked, making of it a ‘model colony’, with all its bad sides: segregation, white superiority complex, and the positive ones: Africans had the best health service of any colony and free primary schooling was compulsory. They also built the best transportation network: more than 6500 kms of railways, 125,000 kms of roads, a small portion of it being asphalted, the best aviation network of the continent, except for South Africa - all but destroyed nowadays.

Belgium HAD to grant independence to a territory that was not ready for it - blame the major powers of yore: the US, the Soviet Union, China, France, Britain, and what was then called the Third World, including India, Egypt, the ‘freed’ North African nations, which forced a puzzled Belgium to subject its colony to the greatest bidders. Actually they helped throw that wonderful giant and very advanced ‘colony’ to the dogs, scaring away the Belgian functionaries, until the whole magnificent infrastructure collapsed.

NOTE: unlike the North Africans who continue to blame France for its colonial past, the Congolese, Rwandans and Burundians are usually on excellent terms with the Belgians. The Congolese still call them their ‘uncles’; an endearing word. In Belgium nowadays, the tens of thousands of Black Africans live and work in harmony with the Belgians - My beloved mother had three African nurses, or better said, dames de compagnie, during the seven years of her illness, who became our dearest friends - which is NOT the case with many immigrants of Moroccan origin. Brussels has become the capital of Islamic terrorism of Europe. And yet, Belgium never colonized Morocco; France did. Explain that to me!

After the success of my African books I was pigeonholed as an African storyteller, especially In France and in Belgium, but not in the English-speaking world. The French publishers of my African novels refused to publish my “Zapinette series” or my short-stories in French. I had to look for other small and middle-sized publishers for the latter. The owner of Ginkgo, in Paris, for instance, tells me that “Zapinette" has nothing to do with Albert Russo!!!

I write my own adaptations in French and English. It is mostly a work of transliteration and of re-writing. I can assure you that it takes as much time as writing my original novel.

“MIXED BLOOD” was the original title of the novel, but, le marketing oblige, my new publisher suggested that I change the title, and I did, naming it “ADOPTED BY AN AMERICAN HOMOSEXUAL IN THE BELGIAN CONGO (AAHBC)”; and even though it has a ‘tabloid’ sounding title, I am quite satisfied with it. I want to reach more readers and this is what is important. Actually, the title “MIXED BLOOD”, which is a good title, is too limited in scope, and furthermore, I have discovered in the meantime that a thriller written much earlier had the same title. AAHBC belongs to me… and to me alone.

Unlike many American or British authors, I write short novels. I don’t like to drag on and on, like my Anglo-Saxon peers do, to the point of discouraging me from reading their 400+ page long novels when I reach page 150. Yet, when I am interested, I can read up to 1000+ page books of history, sociology, psychology, science (made easy) …. books. While I am and will always remain an Agnostic, I have about 20 Bibles of all denominations in 5 languages, as well as archaeological books related to the Bible. To me, the Bible, mainly the Torah, which covers 3/4 of the Christian Bible is the world’s first extraordinary Encyclopaedia, with legends, exciting stories, short and long poems, psalms, half truths, and proven facts. I read parts of it regularly … as I read Shakespeare.

I believe that large conventional Anglo-Saxon publishers think that my novels are too short for saleability. That is why I have small publishers for my works in English: they stress quality over quantity. But here again, Random House et al, could make bestsellers out of each one of my novels that form my AFRICAN QUATUOR. Maybe one day a commercial CEO - aren’t they now those who decide which novel will be published or not, instead of the literary editors? - will understand that they have missed out on something, or maybe not. So no, it’s not about the economy, Stupid, it’s all about the lack of perception. To conclude this subject, I am thankful for the Internet, which has lent my books a second and even a third life.

In LÉODINE OF BELGIAN CONGO Albert Russo soars to new literary heights, combining poetic prose with dramatic staging and imaging so descriptive that it transports the reader not only to Central Africa some sixty years ago, but also into individual moments and hours broken down and expanded exponentially so as to command full introspective experience — and which are consequently adopted by the reader as one’s own. In addition, Monsieur Russo is also an historian and a teacher — both supplying the reader with important and sundry information, much of which was never known to most readers (or forgotten), and which is put into contexts perhaps heretofore unimagined. Another rule of writing (or adage) is to “show, not tell”. Well, Albert Russo manages to do both with great proficiency. We both see, hear, smell and learn, by whatever means the author deems necessary and useful — and Russo has a rather large and colorful palette that he works from.

The story itself —yet another powerful study of an individual’s search for identity and, again, beautifully expressed through the emphatic voice, questioning mind and open soul of an adolescent — is centered around Léodine, who is the daughter of Flemish Astrid and of the American G.I. Gregory McNeil (whom she had met in France during WWII) , but who grows up in the Belgian Congo with her mother, after her father died in a plane crash. Astrid eventually falls in love with one Piet Van den Berg. Léodine one day discovers that her family has a “dark secret” — that her natural father had a black great-grandmother, and that she is of “mixed blood”. The story further documents Léodine’s return to the Congo as an adult, her dismay in seeing the results of the aftermath of the genocide in Rwanda (1994), and her subsequent adoption of a Mozambican boy whom she named after her first adolescent lover — Mario-Tende.

I see in this wonderful novel seedlings of the persona Zapinette — the protagonist and heroine — in Russo’s later “Zapinette series”. Chapters five and six of this book are excellent illustrations of Russo approaching the philosophical and ethical larger questions in life through the eyes of an inquiring adolescent, as well as his excellent research and poetic prose.

And I wonder, what is the root and cause of Albert Russo’s fascination with “mixed blood”? The other questions regarding personal and group identity, politics, and cultural differences are — in most cases — perhaps rather comprehensible. Albert Russo is not, himself, of mixed blood — or is he? Is “mixed blood” perhaps an expression of his own mixed cultural heritage — or does the author have more to reveal to inquisitive readers who finally want to know his answer to this question?

I felt compelled to ask Monsieur Russo what is the source and raison d´être of his previous fascination with “mixed blood”, and how this particular topic was received by readers, the media and publishers at the time. This is what he has responded:

I became convinced that I was of mixed blood during the years of my secondary schooling in Usumbura / Bujumbura, once I started attending the Athénée Royal Interracial - where I had white, black and Asian classmates (a rarity in the colonies, in fact it was exceptional; now I deem it a privilege Whites in the other colonies did not have), not while I was still a child. My childhood left me with very bad memories, because of the nastiness and the jealousy of my father's Italian-Sephardic family towards my beloved mother - "the stranger, the foreigner" - who was much better educated than them, who spoke English - they called her 'la Inglesa'! in a derogatory tone -, a language they couldn't understand, and who, furthermore, played the piano beautifully - "who does she think she is, pummeling the piano notes like that, and giving us headaches with her Chopin, Beethoven and Black American music?"

In my own family, I already felt estranged: different languages, different backgrounds, conflicting cultures. Later on I learned that not only my families were of different religions - Jewish, Christian, and Animist - but also of different races, since I also have cousins of mixed-blood (white / black) in the Congo and in Zimbabwe.

Going back to my novel MB, later known as AAHBC, my peers, as well as new students and new professors of Literature who may one day read that novel or the complete “AFRICAN QUATUOR", might ask themselves, whether the protagonist and the other main characters who appear in AAHBC are real, or come from my imagination. They existed all right. Harry Wilson (not his real name) was an acquaintance of my parents, but it is only as a young adult that I understood who he really was: a homosexual. And yes, he did adopt a mulatto boy (again, Léopold was not his real name). As for Mama Malkia (not her real name here too), she was one of our cook's two wives, the older one. Bigamy was not permitted in the Belgian Congo, but my father convinced the colonial administrator to close an eye, which he did. This is also an example of the flexibility of the Belgians in the Congo. Whereas mixed marriages were looked down upon, they existed, and at primary school I remember having had several mulatto classmates. The latter studied and played with us quasi-normally. Our teachers condemned any blatant discrimination and punished the pupils who were caught insulting them. Mixed classes started existing in the mid-nineteen-fifties, at secondary school and in the brand new and beautiful universities, like Lovanium in Léopoldville and the University of Elisabethville. This is to show and to prove the benevolence of the Belgians, compared to all the other colonialists, whether British, French, Portuguese or Spanish. Which again, does not mean that the Africans were on an equal footing. Until the mid-fifties, they were considered 'eternal children'. I should also stress the fact that during the seventeen years I spent in Belgian-ruled Africa, I have never seen a black man either being hit or thrashed. Those who committed petty crimes were sent to prison for a few weeks. And yes, they were scared of the 'kaboke' (police), who could also be an African. Here, it is also true that some white people took advantage of that fear and threatened them to call a kaboke. But never, ever was there anything similar to the KKK in America, lynchings or killings. There had been before my birth a few uprisings in smaller towns, and there, the Force Publique did kill dozens of Africans to quash the so-called rebellions. I personally never witnessed such events. I repeat, it is true that the big Belgian and foreign companies earned millions of dollars doing business in the Congo, but it is also true that the majority of white functionaries were not rich people and that the Africans largely benefitted from a health service, second to none (much better than even in rich South Africa, for instance) and free primary schooling for Africans, both in their native tongue and in French. Actually these Africans, under the Belgians, were the best educated of all colonies. The big mistake of the Belgian colonial administration, which unlike the others had no colonial experience and proved to be quite naive, was that it started educating an African elite much later than, let's say the British or the French. This being said, the elites were a tiny minority in the British and French colonies, while the masses of Africans were very neglected, compared to what happened in the Congo and in Ruanda-Urundi. With all theses explanations, I still am a fervent anti-colonialist, but I cannot let people write untruths. The rest of the world, lead by the Anglo-Saxons, prefer, even today, to erase the history of the Belgian Congo, and still only refer to Léopold II and to Conrad's masterpiece 'The heart of darkness', which has nothing to do with the Belgian Congo, since it was written during Léopold II's era. I despise liars and so-called “historians” who claim to be experts on colonialism; many of them are ideologues who distort historical facts. Nothing is ever black and white - isn’t that ironically appropriate here?

The other big irony is that in 1958 - only two years before Congo-Léopoldville’s Independence, an International Commission came to the Congo and lauded the Belgians for their ‘magnificent’ work vis-à-vis the African population. Then, when the whole infrastructure collapsed, weeks after the Congo’s Independence in 1960, and tribal wars erupted such as I had never before witnessed, the Belgians began to be called the cruelest colonialists that ever existed!!!

Last, but not least, I wish to conclude on a very personal note. My own father, during his 35-odd years of living in the Congo and Ruanda-Urundi used to spend half of every week in the bush, visiting Africans and Belgians in villages. Often his car broke down and often he was the guest of African chiefs, sleeping in huts and sharing their meals. He could have been killed and no one would have found out how or where. This is to tell you how safe the Congo was, not because of fear, but because they felt protected. When I left Africa at the age of seventeen, I can only remember smiles and good humor. Yes, I can say it: the great majority of Africans were happy with the Belgians, who had eradicated many of the deadly diseases, which have now returned. And yes, todays’ Congolese live in poverty and sickness such as I had never before seen. In the last ten years, six million+ Congolese have died, either because of tribal feuds, conflicts between rebels and the government forces, or because of illness. The Congo today is also known for having the highest percentage of rapes in the world and the UN - that useless ‘grand machin’, as Charles De Gaulle justly called it - has sent the largest contingent of any country, spending billions of dollars ….and letting people be killed, often taking advantage themselves of the soil’s bounty, and raping women. You will never hear or read such facts, because speaking of them is very politically incorrect. Damn political correctness, a terrible and often noxious idea which America spread around the world. Actually, I believe the USA, which has saved Europe and Asia from the Nazis and the Japanese fascists, has committed crimes much bigger than what they say about the Belgians. One crime doesn’t excuse another crime.

I know that what I just wrote will astound and even infuriate university professors around the world, yes even in Africa. I say “be damned” to whomever treats me as a racist or a colonialist. My Congolese, Rwandan and Burundian brethren are there to defend me, from Lubumbashi to Likasi and Kinshasa - and by the way, they created a Wikipedia page about me in Lingala, one of the five major African languages of that huge country, the lingua franca being French -, from Bujumbura to Muramvya (both in Burundi) and Kigali, the capital of Rwanda. Some Hutu and Tutsi still blame the former Belgian administration for their ‘divide and rule’ policy - the Hutu in Rwanda and the Tutsi in Burundi. This is probably true, but it never was the Belgians who incited the Hutu to kill almost a million Tutsi and moderate Hutu in 1994! Actually, during their administration they never allowed the Hutu and the Tutsi to murder each other.

Recently I was approached by the BBC for an interview about the Belgian Congo, but they didn’t like what they heard since they retained their clichés and untruths, and I told them to go to hell. Here we are talking of the so-called prestigious and world respected BBC, which — by the way —did air one of my African stories a few years ago.

Speaking of clichés, a few years ago, in Oslo, I met a nice Asian reviewer, we sympathized and she gladly accepted to write about LBC. Her comments were very positive, except when she concluded the review, saying that, being a white person, I could never put myself in the shoes of Africans. How wrong she was - with her cliché -, of course she didn’t know anything about my real background. So I can excuse her.

A last anecdote - the anti-cliché -: At the beginning of the new millennium, a friend of mine living in London, offered MB / AAHBC to the Nigerian Ambassador in Great Britain. “Funny that I have never heard about that Congolese writer, Albert Russo — he is probably himself of mixed blood, he knows his subject almost like a historian. Thank you so much.” My friend added with a smile, “yes he is Congolese, but rather of the pale type.” “An albino?” “No … white, with blue eyes.”

Albert Russo is indeed a very prolific writer. I have asked him to respond to several questions regarding work routines, publishing experiences with self-publishing and small independent publishers, self-marketing, and his approach(es) to novel-writing. Both wanna-be writers and published authors are often interested in knowing various “tricks-of-the-trade” that established authors employ, as well as the problems they face. Here are some of the questions I have posed, and Russo’s responses to them:

- How many hours do you work each writing day? Do you make work routines? Do you ever get up in the middle of the night to write when ideas occur to you? Do you note ideas in a notebook to use later on, that you carry around or have in your home?

As I said before, I’m a slow writer, but I have a strict discipline and I usually write five days a week, five to seven hours a day, whether I pen one page or more. Right now, having moved to a new country, I can only write a page or two every ten days, which is terribly frustrating, since writing is also a great therapy. I have a file at home with notes and ideas, but I never jot down anything when I am outside of my apartment. What I sometimes do, when I have to wait for a doctor, is write longhand a short poem, but that’s all. Unlike some other writers, I can’t create in cafés, libraries or other public places, because people distract me.

- Is much of your descriptive writing (e.g. details about landscape, flora, fauna, foods, smells, politics etc.) from memory, or from extensive research?

Having grown up in Africa, I have always been moved by the beauty of nature: landscapes, sunsets, fauna and flowers. I remember all these, the instant I think of Africa, the smells, the colors of the trees, the flamboyants, the jacarandas in full bloom. When I tackle politics, I do some research, to be sure I am not writing falsehoods, even if I have a good memory of what happened in Africa.

- Do you work on several writing assignments/projects at the same time (eg. other short stories, poetry, essays), and if so, does your novel-writing inspire these other works?

I can only concentrate on a single project at a time, whether it is a novel or a short story, or even an essay. The only exception is poetry: I take a break and have to write a few verses, it is sort of an existential need. When I spend too long a time away from poetry, I start feeling uneasy.

- Was it in your original plan to publish the four novels as the African Quatuor, or was your decision to group them together one that came after all four had been written?

In reference to my AFRICAN QUATUOR, the decision to reunite my four novels on Africa, it was a joint decision of my publisher l’Aleph and I.

- Have any of the characters or events in your novels been recognized by the real-life persons they are based upon? If so, what have been their responses?

My beloved mother, my sisters, especially, recognized everybody in my books, even though I had changed the names. The extended members of my family, i.e.,aunts, uncles, cousins, etc. never commented on my writing. It is well known that very close people are sometimes afraid of being depicted in a book. Only one uncle and one cousin, who still live in southern Africa, have read and liked my novels. The rest - about 20 people - kept mum.

- Do you have editors who assist you with proofreading in English and French? Are those persons employees of your publishing companies? Does bi-lingual writing entail much personal responsibility for editing and proofreading in other languages?

When I write in French, editors always proofread my manuscripts and they submit their comments to me for approval. In English it was the same with my small and very literary publisher, Imago Press. Otherwise, I am in charge, which is quite a responsibility and a burden. But I prefer it that way, since no one can touch or change what I have written, except for a few lines which a publisher asks me to take out, because I am getting too ‘politically incorrect’. Like those ‘big’ American publishers who demand that you rewrite a book or delete whole paragraphs, or worse chapters, and all of this without any guarantee that, after your excruciating efforts, they will actually accept your manuscript. I deem those editors to be unethical and their decision-makers to be crooks. I have had a horrible experience like that with a major French House, Flammarion. I wrote an essay about that experience in English and won an award for best journalism in California.

- What are your thoughts and experiences about differences between writing literature to be published on the internet vs. in books? Do your styles differ when publishing for persons who read on-the-run or online in opposition to reading a novel that was originally written in a paper format?

I don’t like to write for the Internet, except when I submit poetry and short stories for contests.

When a publisher wishes to publish a whole novel of mine online, I accept it, provided that I get a proper contract. I don’t change a word, since I always hope that the ebook will come out in print in the near future.

- You have both self-published and used many small independent presses for publication. Tell the readers a bit about your experiences with both - how much work do you put into editing your own books, and self-marketing? How do you market your books today (book fairs, tv, radio, internet, Facebook, websites etc.)?

I have had small, average-sized and big publishers, mainly in France. I leave the marketing to the latter two, who, by the way, regularly organize book fairs in Paris, in the provinces and in Belgium, in which I take part. In English I try to help my small publishers, by suggesting ideas. I personally am not good at marketing my own books, even when I self-publish. In this case I sometimes buy marketing services, provided they are within my means. I don’t know how to use social networks, in spite of the fact that I have Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter. And I don’t like to spend too much time on them, inasmuch as I write in two languages and I correct all my Italian books myself, after the publisher has edited them. As I said before, at this moment I don’t even have the time to write regularly for myself.

- Many of your novels could easily be made into theater plays or films. Do you consciously approach writing novels in a cinematic fashion? Have any of your novels been made into plays or films? Which novels would you like to see onstage or at a cinema? And why these particular ones?

Quite a few reviewers wrote that some of my novels were good material for the movie industry. My main French publisher has tried to get MB / AAHBC on screen for years, but nothing has resulted from his efforts in that direction. I know that a few novels of mine would make interesting films: actually my whole AFRICAN QUATUOR, LE CAP DES ILLUSIONS, as well as THE GOSH ZAPINETTE! series; the latter one, more for television than for the big screen. But, with the years, I have realized that, unless you have written a bestseller, and even then, there is no connection whatsoever between the Book industry and Cinema. So I have stopped bothering with the idea.

I do have two of my African novels ‘filmed’ like documentaries, AAHBC and EAE, respectively 90 and over 100 minutes. But those film adaptations do not interest Hollywood.

One of many examples of Russo’s “cinematic writing style” describes a pedophilic experience — as if it were a dream. To describe such an experience in this way is not unnatural, as it is quite human to attempt to disregard the horrible validity of such a personal transgression and intrusion through denial that it really happened. Here Albert Russo’s protagonist (Léodine) shows incredible strength in analyzing the events, ultimately accepting that they - in fact - did occur, and for a time dismissing it, seemingly without further ado. But I can only wonder if Léodine became a “feminist” after that experience — perhaps much as her alter-ego “Zapinette”. Is it possible that Zapinette is a literary split personality? The “dark secret” that Léodine carries as a burden — that of being of “mixed blood” — in my opinion pales against the burden of this particular secret.

Of course, I have many questions for the author. Not only regarding the source of this writing in his own life (or in that of another person that he has known), but also concerning why and how Léodine was able to survive this traumatic experience. Did her own mother’s sexual “looseness” — often accompanied by her abuse of alcohol — enable Leódine to identify with and process this intrusion as “natural” for her — a young woman who is already branded as an undesirable person because she is of “mixed blood”? And even more intimately, knowing that Albert Russo has previously been married and has two grown children whom he loves, how has his “feminism” been affected by and affected his own subsequent homosexual life? These are questions that are perhaps “politically incorrect” and/or “personally improper” to ask of anyone — let alone an author of fiction. But I am going to ask the questions.

Here is the excerpt to which I am referring:

Arnaud poured the last drops of the rosé wine into my glass and exclaimed: “Down it in one gulp! This will be the year!”

I don’t know why but his gesture gave me a fit of the giggles, and soon the two men joined me in a guffaw. I couldn’t put one word after the other, so shaken I was, the situation getting even more difficult when I began to hiccup: “... what are you ... talking about ... I’m ... I’m much too ... young .... to get mmm ... to get married.” I couldn’t even recognize the sound of my own voice, for it reverberated like that of a ventriloquist’s puppet, breaking in the middle of a sentence as if when a soprano, well into her aria, gets interrupted by a sudden attack of asthma, her vocal cords then rasping horrifically.

I conjured up the ridiculous character created by Hergé, the famous Belgian author of Tintin’s adventures, Bianca Castafiore, the stout and rambunctious opera singer who was always prone to attract thieves because of her jewels. This last image made me hysterical. From that moment on, events began to jostle in my head and I can only surmise what followed. I can still see these pictures torn to bits like confetti whirling before my eyes. And in the midst of it all, Rupert carries me to my room, helping me undress, so that I can get into my nightie. Then everything gets blurred. I must have been sound asleep when - was it past midnight, or in the wee hours of the morning? -, a manly face, clean shaven and smelling of menthol approaches me. I open my eyes, at least I think I did, and feel his sweet-scented breath on my cheek. The man’s features strangely resemble those of Rupert’s friend, and he is alone with me in my room. He whispers things that seem to have slipped out of a poetry book, they are so smooth and gentle: “I love your velvety skin .... your hair is pure silk ... I can but kneel at your feet as I kneel before the Virgin Mary ... you’re so pure ... my rosebud .... my ...” These words have the lightness and the quality of Brussels lace.

They envelop me like a light breeze and I welcome it wholeheartedly.

Did I actually feel his finger glide over my breasts, then slip downward, further down, drawing circles around my navel? It followed its course, further down still, oh my God! Then, not one but several fingers clasped the upper band of my pantie, and I began to remonstrate. What he was doing to me wasn’t right. But his murmurs resumed and this time had the levity of rose petals - it felt as if they whirled above me before they gently landed over my eyelids, like a caress which I could not decently repel. I believe his lips brushed mine, the same way a bee gathers pollen from a hibiscus flower. These same lips then pressed themselves tightly between my thighs, and there I felt a warm and pleasant moistness. Did I wet my nightie? I suddenly gasped, flushing with shame. I dared not open my eyes, lest I shock - the stranger as well as myself. I began to whimper and turned my head from left to right, then from right to left, repeating this gesture obsessively, like an automaton, whose batteries are at the end of their tether, aware that its movements would slow down and gradually cease. And the moment froze. “You mustn’t, you mustn’t,” I kept repeating feebly. “You’re ...” I then felt as if someone zipped my lips shut. I was now praying for the man to stop what he was doing, in spite of his being so gentle and so solicitous, but my plea remained unheeded, and worse, or should I say heck, my thoughts began to fly away, far away from the scene, as if what was happening to my body no longer concerned me, or that I had just become a simple spectator. It must have resembled one of those out-of-the body experiences where your mind appears totally split from your flesh. And indeed, I was witnessing the battle my instincts were waging against that foreign element, the adult male, then how they slowly, gradually yielded to the man’s fondling, and how the sin of the flesh, so much decried by the nuns at catechism, was taking place under my gaze. Until now it had been so abstract, so often repeated, that it had almost meshed in my mind with the much more trivial and forgettable anecdotes of life. But suddenly, I sat petrified, for without warning, something began to rub against me, at first soft then becoming very hard and taking on a monstrous consistence. It went on rubbing against my thigh, savagely, probing dangerously upwards, seeking an opening, but my body resisted, fighting as if for dear life. I then heard my nightly visitor huff, calmly at first, then with an increasing agitation that bordered on rage. I felt his hot breath on my skin, it was burning. At last he lashed out, holding on to me with a furious energy, and he let out a long-drawn moan, as if someone had just dealt him a terrible blow. And all of a sudden he went slack. God, what was wrong with him? Was he ... dead? Then, to my horror, I became aware of a warm and sticky liquid spreading between my thighs.

The next day, when Rupert knocked at my door – it was past seven and a half – I was still asleep, or rather slumbering, for I didn’t want to get up, as if I needed that space of time to dilute into the marshes of my mind those, what were they, memories, rantings, which had given me such a shock? Then, mechanically, my hand went to rest over my loins and I felt so relieved to find that it wasn’t smeared. That was enough to discard any residual doubt about what really happened, and I refused to even embrace the thought that I might have gone to the bathroom in the middle of the night in order to wash myself, using a glove. After I brushed my teeth - it took me about ten minutes before I could resume my senses - an incredible brightness filled my head. It was almost like a flood of light invading it, so dense and so powerful, that all the shadows and the particles still clinging to its corners got wiped out, leaving a huge and blinding void in its stead. What was happening to me that my senses were suddenly so exacerbated, so alive? I was seeing everything through a prism of such burning intensity that I asked myself if I hadn’t suddenly been bewitched, for every object that surrounded me became highlighted with extraordinary acuteness: my toothpaste flashed with the fluorescence of an advertising neon, my hair seemed to be spangled with a myriad fireflies, I was hearing myself swallowing in stereophonic sound, I could even ‘see’ and ‘hear’ my skin breathe as if each pore were a miniaturized loudspeaker, and yet in spite or because of this state, I felt paradoxically numbed, cut from reality. It wasn’t out of a sense of fear, or of joy, or even of resentment, no, it was more as if a stranger had slipped into my body, surreptitiously, during the chaotic minutes that preceded my awakening, for I had the impression that my personality had been split, the second me watching over my habitual self with a mixture of indifference and irony. And every so often the intruder would cast me a disdainful and condescending glance, like those self-righteous bourgeois who give you the once-over at a cocktail party, as if to say: “you don’t belong here!”

From this point on, the events unfolded at a surprising speed, like a film reel that the cameraman accelerates, botching down some of the things I had lived, as if my mind had wished to erase them.

And here is Russo’s response:

Indeed I am a staunch feminist and I have always liked the company of women. I despise the gay people who speak of them with disrespect or, worse, with vulgarity, proffering sexual insults in order to demean them. After all, where would they be if there weren’t women? It is they who are the sluts!

I am atypical in too many ways for my own good. I was asexual until the age of 20, yes 20! I didn’t even know there was a difference between heterosexuals and homosexuals, let alone transvestites and transgenders. I was so damn naive, when my teenaged classmates in Africa were already having sexual experiences and made salacious jokes. I always pretended I never heard anything. I was just not interested, as I was not interested in soccer, for example.